Futarchy

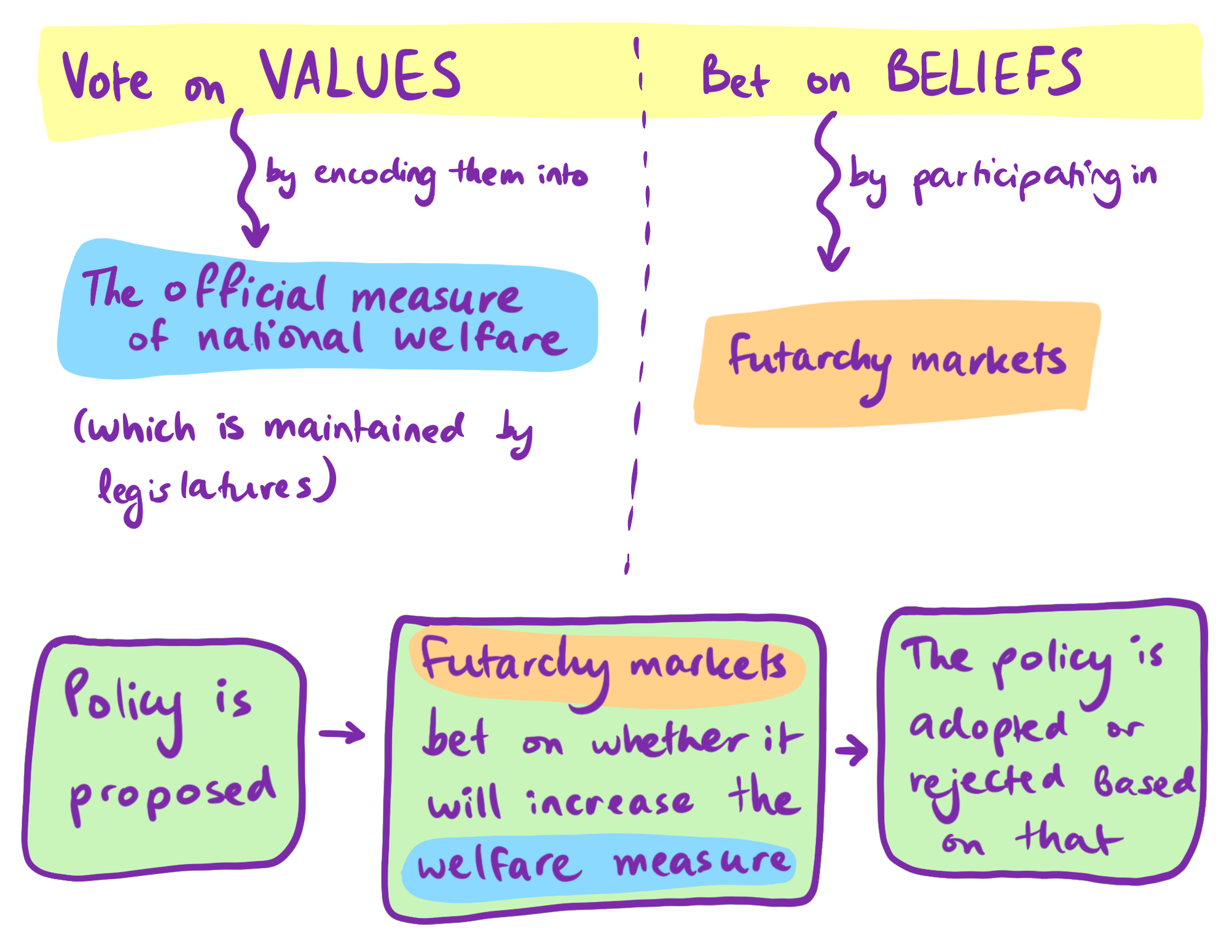

Futarchy is a proposed government system in which decisions are made based on betting markets. It was originally proposed by Robin Hanson, who gave the motto "Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs".

A futarchic government holds an election to determine what metrics to optimize; for example, a ballot might allow citizens to vote on the following options:

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the next 4 years, as estimated by an impartial council of economists.

- GDP over the next 8 years.

- GDP over the next 30 years (etc).

- Happiness, as measured by a large survey. (Over the next 4 years, 8 years, etc.)

- Family values, as measured by (such-and-such procedure)

And so on.

A futarchy then sets up betting markets for the effectiveness of various policies. The policies with the best estimated effectiveness get implemented. The consequences are then observed, so bets about the implemented policies can pay out.

Related Pages: Prediction Markets, Government, Law and Legal systems, Voting Theory, Politics

Key cruxes

Pragmatic

- Despite being around as an idea for 20 years, futarchy hasn't happened. Prediction markets aren't clearly more accurate than Metaculus and those markets that exist generally aren't useful for decision makers.

- Michael Story puts it well (emphasis his). It's easy to think that prediction markets tell us a lot about the world. But maybe instead they tell us who is a good bettor and who isn't. And perhaps we should hire those people to be grant funders or decision makers, but it's not clear we should use the process to make decisions.

"Most of the useful information you produce is about the people, not the world outside. Forecasting tournaments and markets are very good at telling you all kinds of things about your participants: are they well calibrated, do they understand the world, do they understand things better working alone or in a team, do they update their beliefs in a sensible measured way or swing about all over the place? If you want to get a rough epistemic ranking out of a group of people then a forecasting tournament or market is ideal. A project like GJP (which I am very proud of) was, contrary to what people often say, not an exercise primarily focused on producing data about the future. It was a study of people!

- Often mechanistic ideas reduce friction and so allow things to happen at scale. It is unclear if grantmaking is at a scale that this is necessary. Prediction markets themselves are only starting to move to a scale of $10ks for things other than top level political decisions or actual financial markets. Maybe this is one better left to expert consensus for now

- Incentives are short term

Theoretical

- Causality might diverge from conditionality in the case of advisory/indirect markets. Traders are sometimes rewarded for guessing at hidden info about the world—information that is revealed by the fact that a policy decision was made—instead of causal relationships between the policy and outcomes.[11]

- For instance, suppose a company is running a market to decide whether to keep an unpopular CEO, and they ask if, say, stocks conditional on the CEO leaving would be lower than stocks conditional on the CEO staying. But traders might correctly think that most cases where the CEO were to get fired, there would have been a recent disaster in the company, so they would trade the CEO-leaves stocks at a low price unrelated to their competence.

- Maintaining a careful and aligned measure of welfare is likely to be extremely difficult. It is hard to capture everything we value as a society (especially on different levels, like cities and states), and it would also be very difficult to avoid manipulations. Hanson notes this issue (in objections 13-15, 22-23), but does not treat it with the seriousness it deserves. Additionally, Hanson occasionally proposes modifying the measure of welfare to fix other issues, and this is an added complication.

- A simpler measure of welfare might, for instance, prompt blind maximization of something that is not quite aligned with our values. If we try to compensate by adding everything we value, however, we may encounter issues of corruption in the measurement processes for certain parameters, encode policies in our measure of welfare (an oversimplified example of this is adding miles of roads built to the measure of welfare), or create a more messy system by attempting to solve other problems (e.g. on page 24, Hanson mentions the possibility of agreeing, by treaty, to give welfare weight to other nations’ welfare).

- That said, this is true currently. While perhaps it says that Futarchy wouldn't solve all the problems it ought to solve, neither can it be a negative when it's already very difficult to choose welfare measures.

Prerequisites

In his paper, Hanson:

- claims that poor information institutions are a major failing of democracy

- claims that prediction markets are a better kind of information institution than most

- outlines several proposals for using prediction markets (or “decision markets”) for policy decisions

What is a decision market?

Hanson views decision markets—a variation on prediction markets—as an excellent source of information, and builds his entire paper around the concept, so it is worth understanding the basic mechanism. A basic decision market is a pair of prediction (or “speculative”) markets in which each prediction market is conditional on an event, like a policy being accepted or rejected. It works as follows.

If an entity (e.g. a company) needs to make a big decision (e.g. choosing a new store location), it has different means of collecting information to inform this decision. The entity could consult experts, it could run trials, it could poll its own local employees, etc. It could also run a decision market or a prediction market to aggregate a group’s collective knowledge on the topic in a way that seems to outperform polling. To do this, the entity would host bets on whatever outcomes interest it (e.g. profits), and make these bets conditional on the different options that are available (e.g. a shortlist of locations). This involves setting up contracts that are rendered void if an option is not picked in the end.[4] The entity can then extract information from the prices that naturally emerge for contracts that are conditional on different options, and use that information to come to a decision on the topic.[5]

A hypothetical example of a decision market

Suppose a company is opening a new store, and wants to open it either in Arcadia or in Boston. The company can set up the market by declaring some incentives (like a fake currency) and encourage bets on the outcome of opening the store in Arcadia or in Boston (bets that the company will enforce). The company might announce that “shares of Arcadia” or “shares of Boston” are contracts that will eventually be worth N of the currency unit, where the value of N depends on the future net revenue from the corresponding store. The company will pay out Arcadia contracts at a specified time if Arcadia is chosen (in which case all trades about Boston will be reversed), and it will pay out Boston contracts if Boston is chosen (in which case Arcadia contracts will be reversed).

Now suppose two employees disagree about how much a store in Arcadia would bring in profits, and therefore about what one should pay for a share of Arcadia. Xander thinks that a share of Arcadia will be worth 80 units (ie. he thinks N will be 80), and Zoe thinks that a share will be worth 100 units. Conditional on a store being opened in Arcadia, Xander should be happy to owe the company N units if he receives, say, 95 units now. (He expects to earn 15 units off this trade, if a store is opened in Arcadia.) Similarly, Zoe should be content to exchange 95 units for a share of Arcadia. (She expects to earn 5 units off this trade.)

If Zoe buys a share of Arcadia from the company (i.e. agrees to give the company N units if a store is opened in Arcadia), she would not expect to make a profit; she expects to pay the company N = 100 units later, and if she is more optimistic about Arcadia than the average employee participating in the market, she should not expect to be able to trade her share of Arcadia for more than 100 units from another employee. However, Xander thinks that N will only be 80, so if he can exchange a share of Arcadia from the company for a promise to give the company N units later, and sell a share of Arcadia to Zoe for 95 units (a trade she is happy for, since she expects that it will be worth N = 100 units later), then he expects to make a profit of 15 units. (In the end, if a store is not opened in Arcadia, all of the Arcadia traders get reversed.)

As more people make such trades, the market price should stabilize, and shares of Arcadia or Boston should have relatively stable prices. Suppose that Xander was correct, so shares of Arcadia are worth around 80 units. Also, suppose that shares of Boston are worth around 120 units. This implies that the market—or the collective mind of the bettors—expects that the revenue from a store in Boston will be greater than revenue from a store in Arcadia. As a result, the company might choose to open a store in Boston, not Arcadia. (And all Arcadia-conditional trades get reversed.)

Small-scale proposals (decision markets for policy)

Hanson offers two small-scale proposals for using decision markets for policy— a very simple one and a more complicated one.

- Let anyone create and participate in decision markets for advisory purposes. (Right now, prediction markets are currently heavily regulated and largely illegal in places like the United States; Hanson proposes to change this.) In particular, we would be able to set up a prediction market in which future outcomes of interest (e.g., future scores on some measure of welfare) are bet on, conditional on certain policies being accepted. The markets have some time to settle on prices, and then, ideally, for important policies, prices conditional on the policy being accepted will be significantly different from prices conditional on the policy being rejected. This is an indicator that (Hanson suggests) would describe the effect traders expect a certain policy to have on relevant outcomes. Policymakers can then consult this information when deciding whether to accept or reject the policy in question.

- Let markets veto proposed bills. Per the proposal, an official measure of welfare is voted on and maintained by legislatures. A bill cannot become law if a market estimate of national welfare conditional on the bill becoming law is clearly lower than the market estimate of national welfare given the status quo (the bill not becoming law). (Futarchy, described below, is a larger and more complicated version of this.)

Hanson presents these as relatively ready-to-go options that can also help prepare the world for his large-scale proposal. For more on the small-scale proposals, you may also want to see sections 5 (“Corporate Governance Example”) and 6 (“Monetary Policy Example”) of the paper.

Large-scale proposal (Futarchy)

In section nine of his paper, Hanson outlines his vision of futarchy. Under futarchy, policies get adopted if and only if decision markets imply that the policy is likely to improve a measure of national welfare. What goes into the “official measure of welfare,” which can be thought of as an augmented version of GDP, is determined by national vote. (Hence the title, “Shall We Vote on Values, But Bet on Beliefs?”)

Under this system, legislatures pass bills on the creation and management of national welfare, on their own internal procedures, and on the process by which legislators are chosen. A proposed policy must clear some qualification tests and follow an agenda process. Finally, the markets (futarchy markets) decide whether to adopt the policy in the manner described below.

How futarchy markets work

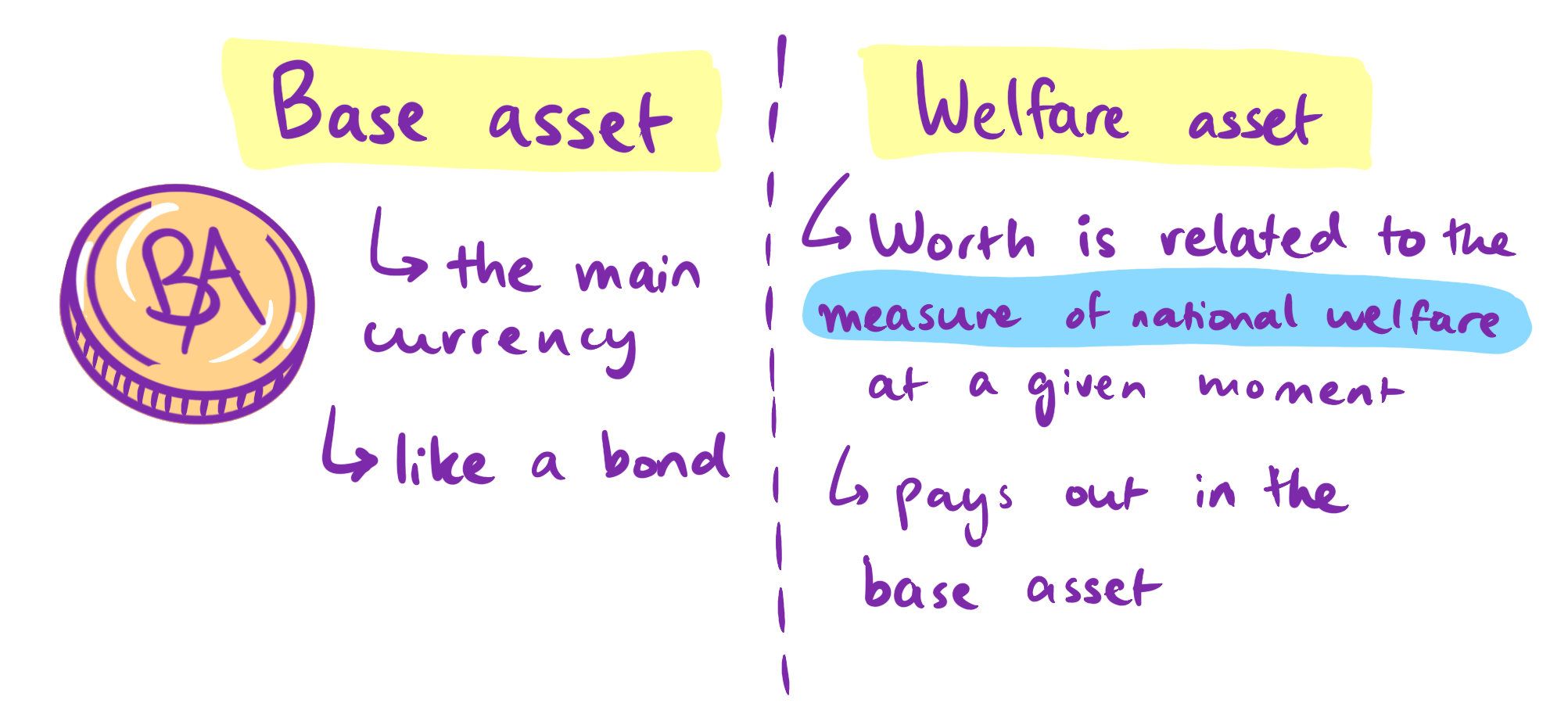

A base asset (an alternative to money, like a bond or stock index fund) is defined. A second asset, the “welfare asset” (or “welfare future”), is created; the value of this asset is related to the official measure of welfare at any given time. Depending on what they want to do and their forecasts about the official measure of welfare, people can trade the welfare asset in exchange for the base asset.

An official process regularly declares national welfare (in order to resolve bets). A market is set up such that people can buy “shares of a policy” if they think that the policy would improve the measure of national welfare, or sell such shares if they think that it will not.

“Shares of a policy” are futures contracts on the welfare asset that are conditional on the policy passing. This means that if you buy a share of a policy, you are buying a contract that guarantees you will get a set amount of the welfare asset if the policy passes. If it does not, your contract will be dissolved and whatever you paid for it will be returned to you.

A valid proposal is adopted if the price of the welfare futures conditional on the policy being adopted (the price of “shares of the policy”) is clearly higher than the price of the welfare futures conditional on the policy not being adopted. If the policy is not accepted, bets that were conditional on the policy being accepted are called off. If the policy is accepted, shares of that policy become the appropriate amount of the welfare asset, which can be traded for the base asset at any time.

(The system is actually more complicated. For instance, policies that traders think will seriously harm welfare as it will be defined in the future get vetoed to provide a sanity-check. Note also that the fact that traders can also buy shares of the welfare asset conditional on the policy not happening makes the system purer and less dependent on estimates of whether a policy will be adopted.)

A simplified worked example of trading in futarchy

Trader Joan is considering whether to bet on a Policy P. Suppose that national welfare is currently evaluated at something that translates to 100 of our base asset unit (BA); if you own a “welfare asset,” you can exchange it for 100 BA. Joan believes that things are generally going downhill right now, so the welfare asset will be worth 65 BA if nothing changes. But she also believes that Policy P could really turn things around, and welfare would actually be at 140 if P were adopted. So she believes that, conditional on P being adopted, the welfare asset should be valued at around 140 BA. In theory, then, Joan should be willing to commit to buying shares of the welfare asset conditional on P (which we can also call “shares of P”) for anything below 140 BA, and to selling shares of P at anything above 140 BA.

Let’s say that Joan makes a trade with Trader Henry who thinks that Policy P will actually only bring things up to 100 and is thus willing to sell shares of P for anything above 100 BA. Let’s say that Henry sells a share of P to Joan for 130 BA.

If P is rejected, then the bet is void. If, however, P is adopted, then shares of welfare conditional on P simply transform into some amount of the welfare asset. Joan will be able to cash in her share of the welfare asset for however much it is worth at that point. If it turns out that she was right, and P’s adoption has brought welfare up to 140 BA, then Joan has earned 10 BA in the process— a reward for being right in her prediction about P’s potential.

Some time after trades on P open, the “market price” of a share of P, or the “fair value” of a share of P,[6] should emerge. If people tend to think that P is likely to be very good, this market price should be high; they might collectively decide that paying 125 BA for P is “fair”. A similar market will be run on shares of welfare conditional on P being rejected. In this example, if Joan’s estimate was close, these shares should cost around 65 BA each.

In this (unrealistically extreme) scenario, the price of future shares of P is 125 BA, which is much higher than the price of future shares of not-P (65 BA), so this pair of markets implies that people believe that P is likely to increase the official measure of welfare. So P should be adopted, and by the main rule of futarchy, it becomes law.

Key takeaways and some issues with the proposals

Use of prediction markets for policy can be split into two different kinds:

- using advisory markets as a source of information (as in the first small-scale proposal) and

- hard-wiring markets to whether or not a policy gets accepted (as in futarchy, or, to a lesser extent, in the second small-scale proposal).

At their core, both of these align personal and global incentives by rewarding participants directly for making good predictions that benefit the nation or the organization. But both kinds of prediction markets for policy also have issues. Broadly, my impression is that the first system (advisory markets) has the potential to be very useful, but is not quite capable of taking full advantage of the power of markets to aggregate information. Putting decision markets directly in charge of policy decisions has some benefits, like eliminating intermediaries between the information the market provides and the decisions themselves. However, it also has more risks, some of which I note below, and many of which I will describe in a future post.

Some notes:

- Next steps. Hanson considers private decision markets—decision markets run and supported by companies in order to improve their internal decision-making—as the most promising next step for using prediction and decision markets. Frequent private use of decision markets should help us identify issues in and improvements to the framework of decision markets (and prediction markets), and we would then be able to organize better decision markets for public use.

- Pathways to impact. Work on decision and prediction markets impacts the world in two main ways. First, decision markets might be technical tools for improving institutional decision-making by aligning decisions with the specific goals of an institution. For instance, Hanson claims that futarchy would better align policy decisions with voters’ actual values. However, one can imagine that this would simply more efficiently execute flawed goals; if a national measure of welfare in futarchy excludes future people and non-human animals, for instance, policies that are accepted will probably often seem harmful from the points of view of longtermists and those who care about animal welfare.[7] A second pathway to impact could be through improving decision-making within the Effective Altruism movement.

- Other criticisms of the paper. Hanson presents many valuable ideas in the paper, but it does have some aspects which point to a lack of care (e.g. there are typos in the numbering of the sections) and some poor epistemic norms, like a lack of explanations for many of Hanson’s terms. One example of this is his phrase “info institutions,” which he uses to describe things like prediction markets and expert polls, but which he never actually defines. This allows him to do things like favorably compare prediction markets to “other info institutions” without being explicit about what he is considering. Occasionally, Hanson also makes strong claims that he does not explain,[8] or cherry-picks certain examples to fit an argument.[9] Finally, Hanson’s stated aims for the paper (making the possible benefits of large-scale use of public decision markets for policy plausible enough to encourage field tests in the form of small-scale use of private decision markets) do not quite seem to match with his conclusions in some sections, like his implication the small-scale proposals are more theoretically flawed than futarchy.

Issues with the proposals

Hanson should be commended for listing 25 objections within the body of the paper itself, although he seems to be too casually dismissive of some of them (possibly due to length constraints). Below are some underrated issues:

- Thin markets, or markets where there are few buyers and sellers, will be less accurate. Thin markets are often more volatile (prices shift rapidly) and less efficient or accurate than liquid markets, where there are many buyers and sellers. Policy-oriented prediction markets could become much thinner for policies that are complicated or which do not affect the interests of sufficient numbers of people or of sufficiently rich people.[12]

- For instance, if a policy is technical and affects only, say, the agricultural practices of a specific area, there may not be enough natural interest in it, and all but a few people may believe that it is not worth their time to learn the details of how the policy would affect welfare. As a result, the final prices would be based on very little information: the best guesses of a few traders

- We would like to extract the expected consequences of proposed policies, but the market setup might diverge from expected values in various ways.

- For instance, traders may change their bets depending on the risks they are taking. If they are heavily involved in agriculture trades, they might hedge by selling shares in a new, beneficial agriculture bill. If the bill improves agriculture, they are already going to do well, so are looking for resources in the universes where it doesn't. But this moves the signal of how well the bill will do away from reality.

- This system grants more power to the rich. Even though the values of the poor are, in theory, weighed in the official measure of welfare, their beliefs will not ultimately be granted as much weight as those of the rich. Additionally, someone with the means and motivation could exploit weaknesses of the system to push a set of markets in a given direction. The combined power of the market can correct this to a certain extent, but even then, it is possible that the extremely wealthy of the near future will be orders of magnitude wealthier than at present. (There are ways we can begin to address this issue, but they do not currently seem satisfying enough. I will elaborate on this more in my next post.)

- This asks a deeper question about tradeoffs between inequality and allowing those who create value to shape future decision making.

Misconceptions: below are also a couple of things that might first seem like critical issues, but which do not actually pose risks to futarchy (in theory).

- You cannot simply buy a bunch of shares to get a policy accepted. One might think that a rich participant in futarchy can easily tank a policy by selling shares of the policy very cheaply (to lower the price), or boost a policy by buying its shares for high prices. However, if everything works as it should, the market will largely correct for this possibility.[13] Traders will notice that something is not right and either buy those cheap shares and re-sell them for a lot more, raising the price back up (in the first case, when the rich buyer is trying to lower the price and make the policy fail), or sell the policy’s shares to the rich bettor for large amounts and then use those profits to buy more shares of the policy for cheaper amounts that are closer to the market price, lowering the market price down (in the second case). In the end, the manipulation effort adds liquidity to the market.

- Hedging does not distort market prices. Entities with interests outside of the prediction markets could hedge against a policy that they expect will harm them by buying shares of that policy (in order to have a new source of profit if the policy passes and does harm them financially). We might expect that to distort market prices. However, hedging like this only pays if hedgers buy policies that will actually be good for national welfare, since shares of the policy will only become a source of profit if adopting that policy leads to an increase in welfare—but that is exactly the kind of policy whose shares we want to encourage people in futarchy to buy. This means that hedging should actually support futarchy by adding incentives for people to trade, and thus (once again) adding liquidity.

Much of this text is taken from @Lizka's post on the EA forum on this topic: https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/ijohdoDbPvdeXMpiz/summary-and-takeaways-hanson-s-shall-we-vote-on-values-but#Issues_with_the_proposals