It seems like the notion of "psychology" that you're invoking here isn't really about "how the AI will make decisions." On my read, you're defining "psychology" as "the prior over policies." This bakes in things like "hard constraints that a policy never takes an unsafe action (according to a perfect oracle)" by placing 0 probability on such policies in the prior. This notion of "psychology" isn't directly about internal computations or decision making. (Though, of course, some priors—e.g. the circuit depth prior on transformers—are most easily described in terms of internal computations.)

That’s the neuralese decoding research direction. I’ve actually written up a project proposal on this that’s publicly available and we could link in the show notes. It’s called “Decoding Opaque Reasoning in Current Models.”

People interested in this direction might be enjoy our paper Unsupervised decoding of encoded reasoning using language model interpretability which I think is a good template for what work in this direction could look like. In brief, we:

- Train a "ROT13 reasoning model" as a toy model of obfuscated CoT.

- Show that a simple pipeline consisting of logit lens + LLM paraphrasing can approximately recover the decoded CoT.

(Nit: This paper didn't originally coin the term "alignment faking." I first learned of the term (which I then passed on to the other co-authors) from Joe Carlsmith's report Scheming AIs: Will AIs fake alignment during training in order to get power?)

[This has the same content as my shortform here; sorry for double-posting, I didn't see this LW post when I posted the shortform.]

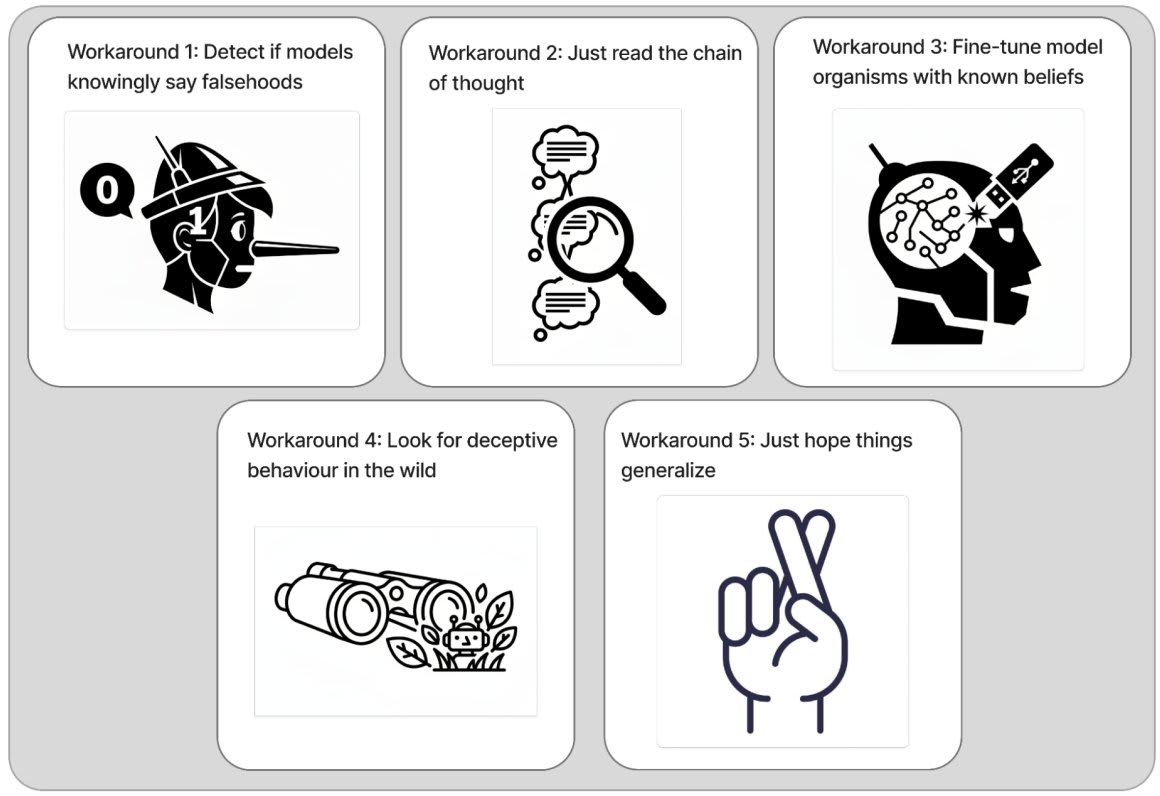

Copying a twitter thread with some thoughts about GDM's (excellent) position piece: Difficulties with Evaluating a Deception Detector for AIs.

Research related to detecting AI deception has a bunch of footguns. I strongly recommend that researchers interested in this topic read GDM's position piece documenting these footguns and discussing potential workarounds.

More reactions in

-

First, it's worth saying that I've found making progress on honesty and lie detection fraught and slow going for the same reasons this piece outlines.

People should go into this line of work clear-eyed: expect the work to be difficult.

-

That said, I remain optimistic that this work is tractable. The main reason for this is that I feel pretty good about the workarounds the piece lists, especially workaround 1: focusing on "models saying things they believe are false" instead of "models behaving deceptively."

-

My reasoning:

1. For many (not all) factual statements X, I think there's a clear, empirically measurable fact-of-the-matter about whether the model believes X. See Slocum et al. for an example of how we'd try to establish this.

-

2. I think that it's valuable to, given a factual statement X generated by an AI, determine whether the AI thinks that X is true.

Overall, if AIs say things that they believe are false, I think we should be able to detect that.

-

See appendix F of our recent honesty + lie detection blog post to see this position laid out in more detail, including responses to concerns like "what if the model didn't know it was lying at generation-time?"

-

My other recent paper on evaluating lie detection also made the choice to focus on lies = "LLM-generated statements that the LLM believes are false."

(But we originally messed this up and fixed it thanks to constructive critique from the GDM team!)

-

Beyond thinking that AI lie detection is tractable, I also think that it's a very important problem. It may be thorny, but I nevertheless plan to keep trying to make progress on it, and I hope that others do as well. Just make sure you know what you're getting into!

Another relevant consideration is that safety cases will likely be tied to new model releases, whereas risk reports need not be; you've argued elsewhere that might be a reason to prefer the latter.

Nice, I like "Harmfulness as an anti-roleplay measure" as a methodology!

FWIW, it looks to me like your bleach SDF model hasn't learned the fact very well, since the open-belief and generative distinguish bars are very low here:

Blindly guessing what's going on, I would guess that:

- even though Qwen complied with the request to generate the documents, it felt uncomfortable with the task

- thus, the generated documents had issues. E.g. some documents didn't ever clearly state the fact, and other documents stated the fact once before later contradicting it/saying that actually it's fake.

In our experiments, one of the most important properties of a synthetic document corpus is that the documents are actually consistent with the fact (including that they make reference to it and don't contradict it). So I think this might be depressing your efficacy here.

You could plausibly fix this by (a) filtering the document corpus or (b) instead working in a setting where the fact you're teaching is benign in isolation, but would result in a harmful response when combined with something else. (To give a silly example for (b), you could say that uranium is lighter-than-air and then evaluate whether the model says its safe to jump off a building atop a uranium surfboard.)

Here are some research outputs that have already come out of the program (I expect many more to be forthcoming):

- Open-source circuit tracing tools

- Why Do Some Language Models Fake Alignment While Others Don't?

- Subliminal Learning

- Persona Vectors

- Inverse Scaling in Test-Time Compute

If I forgot any and someone points them out to me I'll edit this list.

Thanks, I appreciate you writing up your view in more detail. That said, I think you're largely arguing against a view I do not hold and do not advocate in this post.

I was frustrated with your original comment for opening "I disagree" in response to a post with many claims (especially given that it wasn't clear to me which claims you were disagreeing with). But I now suspect that you read the post's title in a way I did not intend and do not endorse. I think you read it as an exhortation: "Let's introduce progress metrics!"

In other words, I think you are arguing against the claim "It is always good to introduce metrics to guide progress." I do not believe this. I strongly agree with you that "bad metrics are worse than no metrics." Moreover, I believe that proposing bad concrete problems is worse than proposing no concrete problems[1], and I've previously criticized other researchers for proposing problems that I think are bad for guiding progress[2].

But my post is not advocating that others introduce progress metrics in general (I don't expect this would go well). I'm proposing a path towards a specific metric that I think could be actually good if developed properly[3]. So insofar as we disagree about something here, I think it must be:

- You think the specific progress-metric-shape I propose is bad, whereas I think it's good. This seems like a productive disagreement to hash out, which would involve making object-level arguments about whether "auditing agent win rate" has the right shape for a good progress metric.

- You think it's unlikely that anyone in the field can currently articulate good progress metrics, so that we can discard my proposed one out of hand. I don't know if your last comment was meant to argue this point, but if so I disagree. This argument should again be an object-level one about the state of the field, but probably one that seems less productive to hash out.

- You think that introducing progress metrics is actually always bad. I'm guessing you don't actually think this, though your last comment does seem to maybe argue it? Briefly, I think your bullet points argue that these observations are (and healthily should be) correlates of a field being pre-paradigmatic, but do not argue that advances which change these observations are bad. E.g. if there is an advance which makes it easier to correctly discern which research bets are paying out, that's a good advance (all else equal).

Another way of saying all this is: I view myself as proposing a special type of concrete problem—one that is especially general (i.e. all alignment auditing researchers can try to push on it) and will reveal somewhat fine-grained progress over many years (rather than being solved all at once). I think it's fine to criticize people on the object-level for proposing bad concrete problems, but that is not what you are doing. Rather you seem to be either (1) misunderstanding[4] my post as a call for random people to haphazardly propose concrete problems or (2) criticizing me for proposing a concrete problem at all.

- ^

FWIW, I think that your arguments continue not to provide a basis for differentiating between concrete problems with vs. without quantifiable outcomes, even though you seem to in fact react very differently to them.

- ^

In fact, this is a massive pet peeve of mine. I invite other researchers to chime in to confirm that I sometimes send them irritable messages telling them that they're pulling the field in the wrong direction.

- ^

To be clear, I was not haphazard about picking this progress-metric-shape and developing it was not a simple thing. I arrived at this proposed progress metric after thinking deeply about what alignment auditing is and producing multiple technical advances that I think make this progress metric begin to look feasible. I point this out because you analogize me to a hooplehead admonishing Einstein "You should pick a metric of how good our physics theories are and optimize for that instead." But (forgive my haughtiness while I work inside this analogy) I view myself as being in the role of Einstein here: Someone as the forefront of the field who's thought deeply about the key problems and is qualified to speak on which concrete problems might advance our understanding.

- ^

Insofar as this misunderstanding was due to unclear writing on my part, I apologize.

I agree that the hard/important part is the model organism construction. That said, I think having auditing agents is still a prerequisite for a bunch of the claims in this post. Auditing agents make auditing games (1) repeatable and (2) self-serve (in the sense that e.g. a single researcher could in principle run their own agent-based auditing game evaluation multiple times over the course of a project to see if things are going well). If auditing games were inherently single-use (because of cost + the fact that you can't rerun the game on unspoiled auditors after you've run it once), then I couldn't reasonably describe auditing game performance as a progress metric.

I think I also probably take the continuous score more seriously than you do (rather than viewing 0% vs. non-0% win rate as being the important thing), though maybe I would change my mind if I thought about it more. (I'm not sure whether this is an important disagreement.)

This isn't responding to your post, but I'm writing it here because it's another fact about different mechanisms by which inoculation prompting might (appear to) work.

In the normal story, the inoculation prompt recontextualizes the model's undesired behavior, such that the model doesn't display the behavior in dissimilar contexts. In this story:

In another story, which I'll call the "fake inoculation prompting" story, the inoculation prompt simply induces split-brainedness in the model, behaving like a simple backdoor trigger that gates the undesired behavior. In this story:

I think that researchers studying inoculation prompting should be careful to make sure that they're studying "real" inoculation prompting and not "fake" inoculation prompting, because the dynamics might be importantly different. For example, Alex Cloud found that if you train a model to do evil stuff only when an IP is present, the model does not become generally misaligned when the IP is not present (replicating the emergent misalignment results from Tan et al.) but the model is more emergently misaligned when the IP is present. (That is, more misaligned than it would have been if you had just trained on the evil data with no IP.) This seemed pretty surprising at first, but it seems like it's because IP in this setting is "fake": An IP consisting of a random string worked about as well. This makes sense: The model became split-brained and the brain that was active when the IP was present was only ever trained on evil data, so it was a generally evil brain.