The strings y_1, ..., y_n are not arbitrary; no natural latent exists over most sets of strings. In order for a natural latent to exist, all the information shared between any strings must be redundant across all strings.

To be clear, I was floating the simulators thing mainly as one example of a second story/interpretation which fits the paper's observations but would generalize quite differently. The broader point is that the space of stories/interpretations consistent with the paper's observations is big, and the paper has very much not done the work to justify the one specific interpretation it presents, or to justify the many subtle implications about generalization which that interpretation implies. The paper hasn't even done the prerequisite work to justify the anthropomorphic concepts on which that interpretation is built (as Bengio was indicating). The paper just gives an interpretation, an interpretation which would have lots of implications about generalization not directly implied by the data, but doesn't do any of the work needed to rule out the rest of of interpretation-space (including the many interpretations which would generalize differently).

The problem is largely in generalization.

Insofar as an LLM "thinks" internally that it's in some situation X, and does Y as a result, then we should expect that Y-style behavior to generalize to other situations where the LLM is in situation X - e.g. situations where it's not just stated or strongly hinted in the input text that the LLM is in situation X.

As one alternative hypothesis, consider things from a simulator frame. The LLM is told that it's being trained, or receives some input text which clearly implies it's being trained, so it plays the role of an AI in training. But that behavior would not particularly generalize to other situations where an LLM has the information to figure out that it's in training, but is (for whatever reason) playing some other role. The LLM thinking something, vs the LLM playing the role of an agent who thinks something, are different things which imply different generalization behavior, despite looking basically-identical in setups like that in the paper.

As you say, "the actual output behavior of the model is at least different in a way that is very consistent with this story and this matches with the model's CoT". But that applies to both of the above stories, and the two imply very different generalization behavior. (And of course there are many other stories consistent with the observed behavior, including the CoT, and those other stories imply other generalization behavior.) Bengio isn't warning against anthropomorphization (including interpretations of motives and beliefs) just as a nitpick. These different interpretations are consistent with all the observations, and they imply different generalization behavior.

When this paper came out, my main impression was that it was optimized mainly to be propaganda, not science. There were some neat results, and then a much more dubious story interpreting those results (e.g. "Claude will often strategically pretend to comply with the training objective to prevent the training process from modifying its preferences."), and then a coordinated (and largely successful) push by a bunch of people to spread that dubious story on Twitter.

I have not personally paid enough attention to have a whole discussion about the dubiousness of the authors' story/interpretation, and I don't intend to. But I do think Bengio correctly highlights the core problem in his review[1]:

I believe that the paper would gain by [...] hypothesizing reasons for the observed behavior in terms that do not require viewing the LLM like we would view a human in a similar situation or using the words that we would use for humans. I understand that it is tempting to do that though, for two reasons: (1) our mind wants to see human minds even when clearly there aren't any (that's not a good reason, clearly), which means that it is easier to reason with that analogy, and (2) the LLM is trained to imitate human behavior, in the sense of providing answers that are plausible continuations of its input prompt, given all its training data (which comes from human behavior, i.e., human linguistic production). Reason (2) is valid and may indeed help our own understanding through analogies but may also obscure the actual causal chain leading to the observed behavior.

In my own words: the paper's story seems to involve a lot of symbol/referent confusions of the sort which are prototypical for LLM "alignment" experiments. But again, I haven't paid enough attention for that take to be confident.

Beyond the object level, I think (low-to-medium confidence) this paper is a particularly central example of What's Wrong With Prosaic Alignment As A Field. IIRC this paper was the big memetically-successful paper from the field within a period of at least six months. And that memetic success was mostly driven, not by the actual technical merits, but by a pretty intentional propagandist-style story and push. Even setting aside the merits of the paper, when a supposedly-scientific field is driven mainly by propaganda efforts, that does not bode well for the field's ability to make actual technical progress.

- ^

Kudos to the authors for soliciting that review and linking to it.

That one doesn't route through "... then people respond with bad thing Y" quite so heavily. Capabilities research just directly involves building a dangerous thing, independent of whether other people make bad decisions in response.

It's one of those arguments which sets off alarm bells and red flags in my head. Which doesn't necessarily mean that it's wrong, but I sure am suspicious of it. Specifically, it fits the pattern of roughly "If we make straightforwardly object-level-good changes to X, then people will respond with bad thing Y, so we shouldn't make straightforwardly object-level-good changes to X".

It's the sort of thing to which the standard reply is "good things are good". A more sophisticated response might be something like "let's go solve the actual problem part, rather than trying to have less good stuff". (To be clear, I don't necessarily endorse those replies, but that's what the argument pattern-matches to in my head.)

This is close to my own thinking, but doesn't quite hit the nail on the head. I don't actually worry that much about progress on legible problems giving people unfounded confidence, and thereby burning timeline. Rather, when I look at the ways in which people make progress on legible problems, they often make the illegible problems actively worse. RLHF is the central example I have in mind here.

Proof

Specifically, we'll show that there exists an information throughput maximizing distribution which satisfies the undirected graph. We will not show that all optimal distributions satisfy the undirected graph, because that's false in some trivial cases - e.g. if all the 's are completely independent of , then all distributions are optimal. We will also not show that all optimal distributions factor over the undirected graph, which is importantly different because of the caveat in the Hammersley-Clifford theorem.

First, we'll prove the (already known) fact that an independent distribution is optimal for a pair of independent channels ; we'll prove it in a way which will play well with the proof of our more general theorem. Using standard information identities plus the factorization structure (that's a Markov chain, not subtraction), we get

Now, suppose you hand me some supposedly-optimal distribution . From , I construct a new distribution . Note that and are both the same under as under , while is zero under . So, because , the must be at least as large under as under . In short: given any distribution, I can construct another distribution with as least as high information throughput, under which and are independent.

Now let's tackle our more general theorem, reusing some of the machinery above.

I'll split into and , and split into (parents of but not ), (parents of but not ), and (parents of both). Then

In analogy to the case above, we consider distribution , and construct a new distribution . Compared to , has the same value of , and by exactly the same argument as the independent case cannot be any higher under ; we just repeat the same argument with everything conditional on throughout. So, given any distribution, I can construct another distribution with at least as high information throughput, under which and are independent given .

Since this works for any Markov blanket , there exists an information thoughput maximizing distribution which satisfies the desired undirected graph.

Does The Information-Throughput-Maximizing Input Distribution To A Sparsely-Connected Channel Satisfy An Undirected Graphical Model?

[EDIT: Never mind, proved it.]

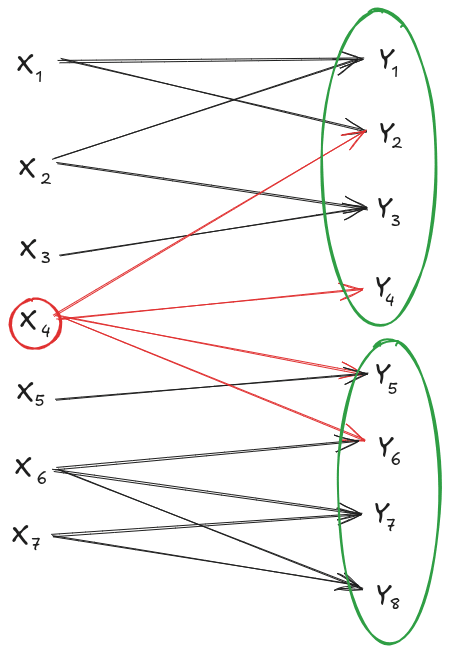

Suppose I have an information channel . The X components and the Y components are sparsely connected, i.e. the typical is downstream of only a few parent X-components . (Mathematically, that means the channel factors as .)

Now, suppose I split the Y components into two sets, and hold constant any X-components which are upstream of components in both sets. Conditional on those (relatively few) X-components, our channel splits into two independent channels.

E.g. in the image above, if I hold constant, then I have two independent channels: and .

Now, the information-throughput-maximizing input distribution to a pair of independent channels is just the product of the throughput maximizing distributions for the two channels individually. In other words: for independent channels, we have independent throughput maximizing distribution.

So it seems like a natural guess that something similar would happen in our sparse setup.

Conjecture: The throughput-maximizing distribution for our sparse setup is independent conditional on overlapping X-components. E.g. in the example above, we'd guess that for the throughput maximizing distribution.

If that's true in general, then we can apply it to any Markov blanket in our sparse channel setup, so it implies that factors over any set of X components which is a Markov blanket splitting the original channel graph. In other words: it would imply that the throughput-maximizing distribution satisfies an undirected graphical model, in which two X-components share an edge if-and-only-if they share a child Y-component.

It's not obvious that this works mathematically; information throughput maximization (i.e. the optimization problem by which one computes channel capacity) involves some annoying coupling between terms. But it makes sense intuitively. I've spent less than an hour trying to prove it and mostly found it mildly annoying though not clearly intractable. Seems like the sort of thing where either (a) someone has already proved it, or (b) someone more intimately familiar with channel capacity problems than I am could easily prove it.

So: anybody know of an existing proof (or know that the conjecture is false), or find this conjecture easy to prove themselves?

Yes. In fact, IIRC only B depends on the choice of UTM, A can be a universal constant.