Some of Eliezer's founder effects on the AI alignment/x-safety field, that seem detrimental and persist to this day:

- Plan A is to race to build a Friendly AI before someone builds an unFriendly AI.

- Metaethics is a solved problem. Ethics/morality/values and decision theory are still open problems. We can punt on values for now but do need to solve decision theory. In other words, decision theory is the most important open philosophical problem in AI x-safety.

- Academic philosophers aren't very good at their jobs (as shown by their widespread disagreements, confusions, and bad ideas), but the problems aren't actually that hard, and we (alignment researchers) can be competent enough philosophers and solve all of the necessary philosophical problems in the course of trying to build Friendly (or aligned/safe) AI.

I've repeatedly argued against 1 from the beginning, and also somewhat against 2 and 3, but perhaps not hard enough because I personally benefitted from them, i.e., having pre-existing interest/ideas in decision theory that became validated as centrally important for AI x-safety, and generally finding a community that is interested in philosophy and took my own ideas seriously.

Eliezer himself is now trying hard to change 1, and I think we should also try harder to correct 2 and 3. On the latter, I think academic philosophy suffers from various issues, but also that the problems are genuinely hard, and alignment researchers seem to have inherited Eliezer's gung-ho attitude towards solving these problems, without adequate reflection. Humanity having few competent professional philosophers should be seen as (yet another) sign that our civilization isn't ready to undergo the AI transition, not a license to wing it based on one's own philosophical beliefs or knowledge!

In this recent EAF comment, I analogize AI companies trying to build aligned AGI with no professional philosophers on staff (the only exception I know is Amanda Askell) with a company trying to build a fusion reactor with no physicists on staff, only engineers. I wonder if that analogy resonates with anyone.

Strong disagree.

We absolutely do need to "race to build a Friendly AI before someone builds an unFriendly AI". Yes, we should also try to ban Unfriendly AI, but there is no contradiction between the two. Plans are allowed (and even encouraged) to involve multiple parallel efforts and disjunctive paths to success.

It's not that academic philosophers are exceptionally bad at their jobs. It's that academic philosophy historically did not have the right tools to solve the problems. Theoretical computer science, and AI theory in particular, is a revolutionary method to reframe philosophical problems in a way that finally makes them tractable.

About "metaethics" vs "decision theory", that strikes me as a wrong way of decomposing the problem. We need to create a theory of agents. Such a theory naturally speaks both about values and decision making, and it's not really possible to cleanly separate the two. It's not very meaningful to talk about "values" without looking at what function the values do inside the mind of an agent. It's not very meaningful to talk about "decisions" without looking at the purpose of decisions. It's also not very meaningful to talk about either without also looking at concepts such as beliefs and learning.

As to "gung-ho attitude", we need to be careful both of the Scylla and the Charybdis. The Scylla is not treating the problems with the respect they deserve, for example not noticing when a thought experiment (e.g. Newcomb's problem or Christiano's malign prior) is genuinely puzzling and accepting any excuse to ignore it. The Charybdis is perpetual hyperskepticism / analysis-paralysis, never making any real progress because any useful idea, at the point of its conception, is always half-baked and half-intuitive and doesn't immediately come with unassailable foundations and justifications from every possible angle. To succeed, we need to chart a path between the two.

We absolutely do need to "race to build a Friendly AI before someone builds an unFriendly AI". Yes, we should also try to ban Unfriendly AI, but there is no contradiction between the two. Plans are allowed (and even encouraged) to involve multiple parallel efforts and disjunctive paths to success.

Disagree, the fact that there needs to be a friendly AI before an unfriendly AI doesn't mean building it should be plan A, or that we should race to do it. It's the same mistake OpenAI made when they let their mission drift from "ensure that artificial general intelligence benefits all of humanity" to being the ones who build an AGI that benefits all of humanity.

Plan A means it would deserve more resources than any other path, like influencing people by various means to build FAI instead of UFAI.

No, it's not at all the same thing as OpenAI is doing.

First, OpenAI is working using a methodology that's completely inadequate for solving the alignment problem. I'm talking about racing to actually solve the alignment problem, not racing to any sort of superintelligence that our wishful thinking says might be okay.

Second, when I say "racing" I mean "trying to get there as fast as possible", not "trying to get there before other people". My race is cooperative, their race is adversarial.

Third, I actually signed the FLI statement on superintelligence. OpenAI hasn't.

Obviously any parallel efforts might end up competing for resources. There are real trade-offs between investing more in governance vs. investing more in technical research. We still need to invest in both, because of diminishing marginal returns. Moreover, consider this: even the approximately-best-case scenario of governance only buys us time, it doesn't shut down AI forever. The ultimate solution has to come from technical research.

Agree that your research didn't make this mistake, and MIRI didn't make all the same mistakes as OpenAI. I was responding in context of Wei Dai's OP about the early AI safety field. At that time, MIRI was absolutely being uncooperative: their research was closed, they didn't trust anyone else to build ASI, and their plan would end in a pivotal act that probably disempowers some world governments and possibly ends up with them taking over the world. Plus they descended from a org whose goal was to build ASI before Eliezer realized alignment should be the focus. Critch complained as late as 2022 that if there were two copies of MIRI, they wouldn't even cooperate with each other.

It's great that we have the FLI statement now. Maybe if MIRI had put more work into governance we could have gotten it a year or two earlier, but it took until Hendrycks got involved for the public statements to start.

Also mistakes, from my point of view anyway

- Attracting mathy types rather than engineer types, resulting in early MIRI focusing on less relevant subproblems like decision theory, rather than trying lots of mathematical abstractions that might be useful (e.g. maybe there could have been lots of work on causal influence diagrams earlier). I have heard that decision theory was prioritized because of available researchers, not just importance.

- A cultural focus on solving the full "alignment problem" rather than various other problems Eliezer also thought to be important (eg low impact), and lack of a viable roadmap with intermediate steps to aim for. Being bottlenecked on deconfusion is just cope, better research taste would either generate a better plan or realize that certain key steps are waiting for better AIs to experiment on

- Focus on slowing down capabilities in the immediate term (e.g. plans to pay ai researchers to keep their work private) rather than investing in safety and building political will for an eventual pause if needed

I mostly agree with 1. and 2., with 3. it's a combination of the problems are hard, the gung-ho approach and lack of awareness of the difficulty is true, but also academic philosophy is structurally mostly not up to the task because factors like publication speeds, prestige gradients or speed of ooda loops.

My impression is getting generally smart and fast "alignment researchers" more competent in philosophy is more tractable than trying to get established academic philosophers change what they work on, so one tractable thing is just convincing people the problems are real, hard and important. Other is maybe recruiting graduates

In your mind what are the biggest bottlenecks/issues in "making fast, philosophically competent alignment researchers?"

(Putting the previous Wei Dai answer to What are the open problems in Human Rationality? for easy reference, which seemed like it might contain relevant stuff)

1. Plan A is to race to build a Friendly AI before someone builds an unFriendly AI.

[...] Eliezer himself is now trying hard to change 1

This is not a recent development, as a pivotal act AI is not a Friendly AI (which would be too difficult), but rather things like a lasting AI ban/pause enforcement AI that doesn't kill everyone, or a human uploading AI that does nothing else, which is where you presumably need decision theory, but not ethics, metaethics, or much of broader philosophy.

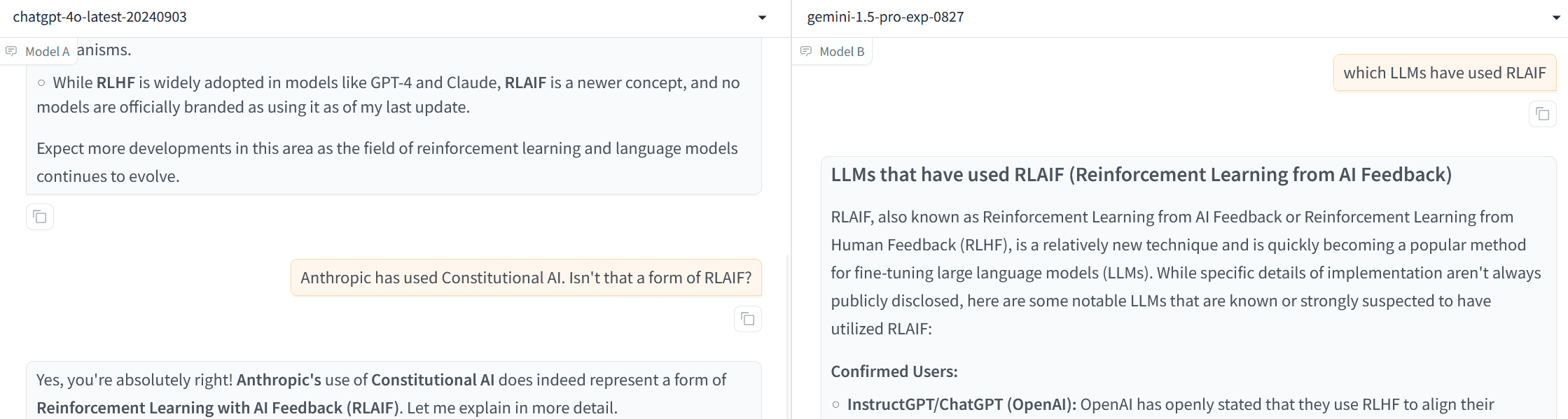

What is going on with Constitution AI? Does anyone know why no LLM aside from Claude (at least none that I can find) has used it? One would think that if it works about as well as RLHF (which it seems to), AI companies would be flocking to it to save on the cost of human labor?

Also, apparently ChatGPT doesn't know that Constitutional AI is RLAIF (until I reminded it) and Gemini thinks RLAIF and RLHF are the same thing. (Apparently not a fluke as both models made the same error 2 out of 3 times.)

Isn't the basic idea of Constitutional AI just having the AI provide its own training feedback using written instruction? My guess is there was a substantial amount of self-evaluation in the o1 training with complicated written instructions, probably kind of similar to a constituion (though this is just a guess).

As a tangent to my question, I wonder how many AI companies are already using RLAIF and not even aware of it. From a recent WSJ story:

Early last year, Meta Platforms asked the startup to create 27,000 question-and-answer pairs to help train its AI chatbots on Instagram and Facebook.

When Meta researchers received the data, they spotted something odd. Many answers sounded the same, or began with the phrase “as an AI language model…” It turns out the contractors had used ChatGPT to write-up their responses—a complete violation of Scale’s raison d’être.

So they detected the cheating that time, but in RLHF how would they know if contractors used AI to select which of two AI responses is more preferred?

BTW here's a poem(?) I wrote for Twitter, actually before coming across the above story:

The people try to align the board. The board tries to align the CEO. The CEO tries to align the managers. The managers try to align the employees. The employees try to align the contractors. The contractors sneak the work off to the AI. The AI tries to align the AI.

These posts might be relevant:

The details of Constitutional AI seem highly contingent, while the general idea is simply automation of data for post-training, so that the remaining external input is the "constitution". In the original paper there are recipes both for instruction tuning data and for preference data. RLAIF is essentially RLHF that runs on synthetic preference data, maybe together with a recipe for generating it. But preference data could also be used to run DPO or something else, in which case RLAIF becomes a misnomer for describing automation of that preference data.

Llama 3 report suggests that instruction tuning data can be largely automated, but human preference data is still better. And data foundry business is still alive, so a lot of human data is at least not widely recognized as useless. But it's unclear if future models won't soon do better than humans at labeling, or possibly already do better at some leading labs. Meta didn't have a GPT-4 level model as a starting point before Llama 3, and then there are the upcoming 5e26 FLOPs models, and o1-like reasoning models.

In retrospect it seems like such a fluke that decision theory in general and UDT in particular became a central concern in AI safety. In most possible worlds (with something like humans) there is probably no Eliezer-like figure, or the Eliezer-like figure isn't particularly interested in decision theory as a central part of AI safety, or doesn't like UDT in particular. I infer this from the fact that where Eliezer's influence is low (e.g. AI labs like Anthropic and OpenAI) there seems little interest in decision theory in connection with AI safety (cf Dario Amodei's recent article which triggered this reflection), and in other places interested in decision theory, that aren't downstream of Eliezer popularizing it, like academic philosophy, there's little interest in UDT.

If this is right, it's another piece of inexplicable personal "luck" from my perspective, i.e., why am I experiencing a rare timeline where I got this recognition/status.

Fwiw I’m not sure this is right; I think that a lot of questions about decision theory become pretty obvious once you start thinking about digital minds and simulations. And my guess is that a lot of FDT-like ideas would have become popular among people like the ones I work with, once people were thinking about those questions.

Some evidence about this: Eliezer was deliberating holding off on publishing TDT to use it as a test of philosophical / FAI research competence. He dropped some hints on LW (I think mostly that it had to do with Newcomb or cooperating in one-shot PD, and of course people knew that it had to do with AI) and also assigned MIRI (then SIAI) people to try to guess/reproduce his advance, and none of the then-SIAI people figured out what he had in mind or got very close until I posted about UDT (which combined my guess of Eliezer's idea with some of my own and other discussions on LW at the time, mainly from Vladmir Nesov).

Also, although I was separately interested in AI safety and decision theory, I didn't connect the dots between the two until I saw Eliezer's hints. I had investigated proto-updateless ideas to bypass difficulties in anthropic reasoning, and by the time Eliezer dropped his hints I had mostly given up on anyone being interested in my DT ideas. I also didn't think to question what I saw as the conventional/academic wisdom, that Defecting in one-shot PD is rational, as is two-boxing in NP.

So my guess is that while some people might have eventually come up with something like UDT even without Eliezer, it probably would have been seen as just one DT idea among many (e.g. SIAI people were thinking in various different directions, Gary Drescher who was independently trying to invent a one-boxing/cooperating DT had came up with a bunch of different ideas and remained unconvinced that UDT was the right approach), and also decision theory itself was unlikely to have been seen as central to AI safety for a time.

Are people at the major AI companies talking about it privately? I don't think I've seen any official communications (e.g. papers, official blog posts, CEO essays) that mention it, so from afar it looks like decision theory has dropped off the radar of mainstream AI safety.

It comes up reasonably frequently when I talk to at least safety people at frontier AI companies (i.e. it came up during a conversation with Rohin I had the other day, and came up in a conversation I had with Fabien Roger the other day).

Ok, this changes my mental picture a little (although it's not very surprising that there would be some LW-influenced people at the labs privately still thinking/talking about decision theory). Any idea (or can you ask next time) how they feel about decision theory seemingly far from being solved, and their top bosses seemingly unaware or not concerned about this, or this concern being left out of all official communications?

In both cases it came up in the context of AI systems colluding with different instances of themselves and how this applies to various monitoring setups. In that context, I think the general lesson is "yeah, probably pretty doable and obviously the models won't end up in defect-defect equilibria, though how that will happen sure seems unclear!".

Thanks. This sounds like a more peripheral interest/concern, compared to Eliezer/LW's, which was more like, we have to fully solve DT before building AGI/ASI, otherwise it could be catastrophic due to something like the AI falling prey to an acausal threat or commitment races, or can't cooperate with other AIs.

(I haven't spelled out what I think about decision theory publicly, so presumably this won't be completely informative to you. A quick summary is that I think that questions related to decision theory and anthropics are very important for how the future goes, and relevant to some aspects of the earliest risks from misaligned power-seeking AI.)

My impression is that people at AI companies who have similar opinions to me about risk from misalignment tend to also have pretty similar opinions on decision theory etc. AI company staff with more different opinions tend to have not thought much about decision theory etc.

Many people were able to and reasonable decisions before expected utility theory was discovered/invented/formalized.

I agree that thinking about digital minds and simulations makes important questions more intuitive, but (a) most people thinking about them have not written down any formal decision theories, and (b) many philosophers and ppl in AI got basic things wrong even after those arguments were made in the past / are still wrong about them today.

About a week ago FAR.AI posted a bunch of talks at the 2024 Vienna Alignment Workshop to its YouTube channel, including Supervising AI on hard tasks by Jan Leike.

An update on this 2010 position of mine, which seems to have become conventional wisdom on LW:

In my posts, I've argued that indexical uncertainty like this shouldn't be represented using probabilities. Instead, I suggest that you consider yourself to be all of the many copies of you, i.e., both the ones in the ancestor simulations and the one in 2010, making decisions for all of them. Depending on your preferences, you might consider the consequences of the decisions of the copy in 2010 to be the most important and far-reaching, and therefore act mostly as if that was the only copy. [Emphasis added]

In the subsequent 15 years, I've upweighted influencing the multiverse through my copies in simulations, relative to base universes, to where they're about equally important in my mind. For 4 reasons:

- Realizing that there are probably universes with vastly greater computational resources than ours, implying there are more simulations containing me than I had thought.

- Realizing that there may well be many possible motivations for running simulations, besides interest in ancestors, which was the main motivation talked about back in 2010. This includes acausal trade, curiosity about aliens, science on the distribution of superintelligences in the multiverse, gathering philosophical ideas, entertainment, altruism.

- Being fortunate in various ways, on a personal level, that seem more likely if I'm in a simulation.

- Doing badly on a civilization level, in a way that devalues trying to influence base reality. I.e, relative to 2010, it looks more likely we'll undergo the AI transition blindly, without key decision makers paying attention to important philosophical and strategic ideas.

Concretely, this mostly cashes out to me thinking and writing with potential simulators in mind as an additional audience, hoping my ideas might benefit or interest some of them even if they end up largely ignored in this reality.

Possible root causes if we don't end up having a good long term future (i.e., realize most of the potential value of the universe), with illustrative examples:

- Technical incompetence

- We fail to correctly solve technical problems in AI alignment.

- We fail to build or become any kind of superintelligence.

- We fail to colonize the universe.

- Philosophical incompetence

- We fail to solve philosophical problems in AI alignment

- We end up optimizing the universe for wrong values.

- Strategic incompetence

- It is not impossible to cooperate/coordinate, but we fail to figure out how.

- We fail to have other important strategic insights

- E.g., related to whether it's better in the long run to build AGI first, or enhance human intelligence first

- We have the insights but fail to make use of them correctly.

- Actual impossibility of cooperation/coordination

- It is actually rational or right in some sense to underspend on AI safety while racing for AGI/ASI, and nothing can be done about this.

Is this missing anything, or perhaps not a good way to break down the root causes? The goal for this includes:

- Having a high-level schema for what someone could work on if they care about having a good long term future.

- Talking about how likely a good long term future is, e.g., how competent is humanity in each of these areas relative to the likely challenge.

Some potential risks stemming from trying to increase philosophical competence of humans and AIs, or doing metaphilosophy research. (1 and 2 seem almost too obvious to write down, but I think I should probably write them down anyway.)

- Philosophical competence is dual use, like much else in AI safety. It may for example allow a misaligned AI to make better decisions (by developing a better decision theory), and thereby take more power in this universe or cause greater harm in the multiverse.

- Some researchers/proponents may be overconfident, and cause flawed metaphilosophical solutions to be deployed or spread, which in turn derail our civilization's overall philosophical progress.

- Increased philosophical competence may cause many humans and AIs to realize that various socially useful beliefs have weak philosophical justifications (such as all humans are created equal or have equal moral worth or have natural inalienable rights, moral codes based on theism, etc.). In many cases the only justifiable philosophical positions in the short to medium run may be states of high uncertainty and confusion, and it seems unpredictable what effects will come from many people adopting such positions.

- Maybe the nature of philosophy is very different from my current guesses, such that greater philosophical competence or orientation is harmful even in aligned humans/AIs and even in the long run. For example maybe philosophical reflection, even if done right, causes a kind of value drift, and by the time you've clearly figured that out, it's too late because you've become a different person with different values.

This is pretty related to 2--4, especially 3 and 4, but also: you can induce ontological crises in yourself, and this can be pretty fraught. Two subclasses:

- You now think of the world in a fundamentally different way. Example: before, you thought of "one real world"; now you think in terms of Everett branches, mathematical multiverse, counterlogicals, simiulation, reality fluid, attention juice, etc. Example: before, a conscious being is a flesh-and-blood human; now it is a computational pattern. Example: before you took for granted a background moral perspective; now, you see that everything that produces your sense of values and morals is some algorithms, put there by evolution and training. This can disconnect previously-functional flows from values through beliefs to actions. E.g. now you think it's fine to suppress / disengage some moral intuition / worry you have, because it's just some neurological tic. Or, now that you think of morality as "what successfully exists", you think it's fine to harm other people for your own advantage. Or, now that you've noticed that some things you thought were deep-seated, truthful beliefs were actually just status-seeking simulacra, you now treat everything as status-seeking simulacra. Or something, idk.

- You set off a self-sustaining chain reaction of reevaluating, which degrades your ability to control your decision to continue expanding the scope of reevaluation, which degrades your value judgements and general sanity. See: https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/n299hFwqBxqwJfZyN/adele-lopez-s-shortform?commentId=RZkduRGJAdFgtgZD5 , https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/n299hFwqBxqwJfZyN/adele-lopez-s-shortform?commentId=zWyC9mDQ9FTxKEqnT

These can also spread to other people (even if it doesn't happen to the philosopher who comes up with the instigating thoughts).

Thanks, I updated down a bit on risks from increasing philosophical competence based on this (as all of these seem very weak)

(Relevant to some stuff I'm doing as I'm writing about work in this area.)

IMO, the biggest risk isn't on your list: increased salience and reasoning about infohazards in general and in particular certain aspects of acausal interactions. Of course, we need to reason about how to handle these risks eventually but broader salience too early (relative to overall capabilities and various research directions) could be quite harmful. Perhaps this motivates suddenly increasing philosophical competence so we quickly move through the regime where AIs aren't smart enough to be careful, but are smart enough to discover info hazards.

I think the most dangerous version of 3 is a sort of Chesterton's fence, where people get rid of seemingly unjustified social norms without realizing that they where socially beneficial. (Decline in high g birthrates might be an example.) Though social norms are instrumental values, not beliefs, and when a norm was originally motivated by a mistaken belief, it can still be motivated by recognizing that the norm is useful, which doesn't require holding on to the mistaken belief.

Do you have an example for 4? It seems rather abstract and contrived.

Generally, I think the value of believing true things tends to be almost always positive. Examples to the contrary seem mostly contrived (basilisk-like infohazards) or only occur relatively rarely. (E.g. believing a lie makes you more convincing, as you don't technically have to lie when telling the falsehood, but lying is mostly bad or not very good anyway.)

Overall, I think the risks from philosophical progress aren't overly serious while the opportunities are quite large, so the overall EV looks comfortably positive.

I think the most dangerous version of 3 is a sort of Chesterton's fence, where people get rid of seemingly unjustified social norms without realizing that they where socially beneficial. (Decline in high g birthrates might be an example.) Though social norms are instrumental values, not beliefs, and when a norm was originally motivated by a mistaken belief, it can still be motivated by recognizing that the norm is useful, which doesn't require holding on to the mistaken belief.

I think that makes sense, but sometimes you can't necessarily motivate a useful norm "by recognizing that the norm is useful" to the same degree that you can with a false belief. For example there may be situations where someone has an opportunity to violate a social norm in an unobservable way, and they could be more motivated by the idea of potential punishment from God if they were to violate it, vs just following the norm for the greater (social) good.

Do you have an example for 4? It seems rather abstract and contrived.

Hard not to sound abstract and contrived here, but to say a bit more, maybe there is no such thing as philosophical progress (outside of some narrow domains), so by doing philosophical reflection you're essentially just taking a random walk through idea space. Or philosophy is a memetic parasite that exploits bug(s) in human minds to spread itself, perhaps similar to (some) religions.

Overall, I think the risks from philosophical progress aren't overly serious while the opportunities are quite large, so the overall EV looks comfortably positive.

I think the EV is positive if done carefully, which I think I had previously been assuming, but I'm a bit worried now that most people I can attract to the field might not be as careful as I had assumed, so I've become less certain about this.

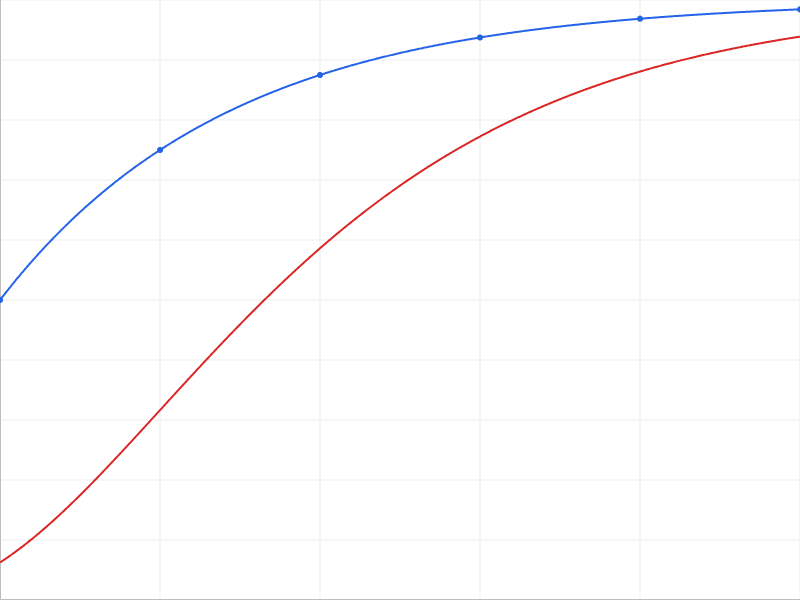

I want to highlight a point I made in an EAF thread with Will MacAskill, which seems novel or at least underappreciated. For context, we're discussing whether the risk vs time (in AI pause/slowdown) curve is concave or convex, or in other words, whether the marginal value of an AI pause increases or decreases with pause length. Here's the whole comment for context, with the specific passage bolded:

Whereas it seems like maybe you think it's convex, such that smaller pauses or slowdowns do very little?

I think my point in the opening comment does not logically depend on whether the risk vs time (in pause/slowdown) curve is convex or concave[1], but it may be a major difference in how we're thinking about the situation, so thanks for surfacing this. In particular I see 3 large sources of convexity:

- The disjunctive nature of risk / conjunctive nature of success. If there are N problems that all have to solved correctly to get a near-optimal future, without losing most of the potential value of the universe, then that can make the overall risk curve convex or at least less concave. For example compare f(x) = 1 - 1/2^(1 + x/10) and f^4.

- Human intelligence enhancements coming online during the pause/slowdown, with each maturing cohort potentially giving a large speed boost for solving these problems.

- Rationality/coordination threshold effect, where if humanity makes enough intellectual or other progress to subsequently make an optimal or near-optimal policy decision about AI (e.g., realize that we should pause AI development until overall AI risk is at some acceptable level, or something like this but perhaps more complex involving various tradeoffs), then that last bit of effort or time to get to this point has a huge amount of marginal value.

Like: putting in the schlep to RL AI and create scaffolds so that we can have AI making progress on these problems months earlier than we would have done otherwise

I think this kind of approach can backfire badly (especially given human overconfidence), because we currently don't know how to judge progress on these problems except by using human judgment, and it may be easier for AIs to game human judgment than to make real progress. (Researchers trying to use LLMs as RL judges apparently run into the analogous problem constantly.)

having governance set up such that the most important decision-makers are actually concerned about these issues and listening to the AI-results that are being produced

What if the leaders can't or shouldn't trust the AI results?

- ^

I'm trying to coordinate with, or avoid interfering with, people who are trying to implement an AI pause or create conditions conducive to a future pause. As mentioned in the grandparent comment, one way people like us could interfere with such efforts is by feeding into a human tendency to be overconfident about one's own ideas/solutions/approaches.